When you pick up a paperback novel and slip it into your bag, you’re holding a piece of technology that’s centuries old. The idea of a small, affordable book designed to travel with its reader seems distinctly modern — a product of 20th-century publishing. Yet, the roots of this idea stretch back over five hundred years to the workshops of Renaissance Venice and, surprisingly, to the island of Crete.

This is the story of how a visionary Venetian printer, Aldus Manutius, and a brilliant Cretan scholar, Markos Mousouros, joined forces to create the world’s first “handbooks” — portable books that changed the course of reading forever. Their motto, engraved beneath a dolphin and an anchor, summed up their philosophy perfectly: “Festina Lente” — Make Haste Slowly.

The Heavyweight Age of Books

Before the printing revolution, books were treasures — hand-copied manuscripts bound in thick leather, adorned with gold leaf, and far too large to carry. A single Bible could weigh as much as a small child. Reading was an act confined to monasteries and noble homes. If you wanted to read, you went to the book, not the other way around.

The arrival of movable type in the mid-15th century changed everything. For the first time, words could be duplicated mechanically rather than copied by hand. Printing houses began to spring up across Europe, and the potential for sharing knowledge grew exponentially. But even then, most printed books were massive and expensive, intended for scholars or wealthy patrons. The average person could hardly afford to own one.

It was in this world — rich in ideas but poor in access — that Aldus Manutius began to dream of a different kind of book.

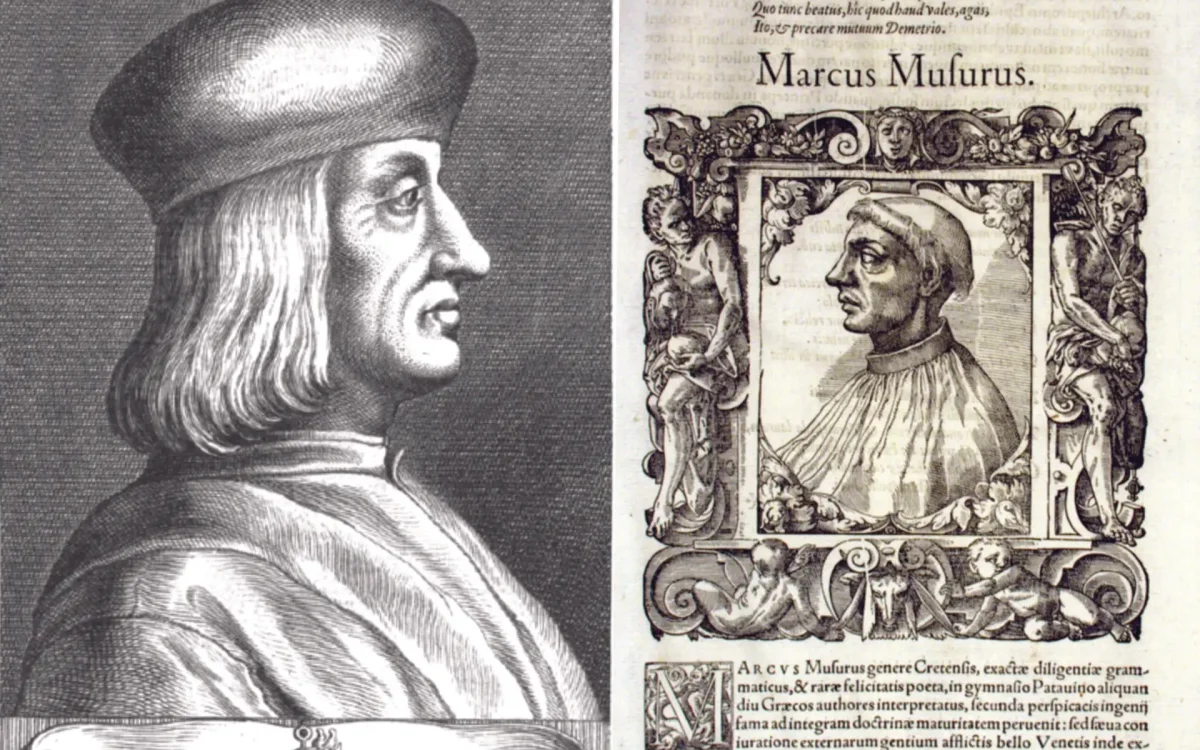

Aldus Manutius was born around 1449 in the Papal States of Italy, but his true calling took shape in Venice, the commercial and intellectual heart of Renaissance Europe. By the time he founded his printing house, the Aldine Press, in 1494, he had one ambitious goal: to preserve and disseminate the masterpieces of ancient Greek and Latin literature.

Aldus was not content to produce enormous, decorative tomes. He wanted to create books that were elegant, readable, and — most importantly — portable. He imagined scholars, travellers, and curious minds carrying small books in their pockets, reading wherever they pleased.

To achieve this vision, he needed two things: the right texts and the right technology. For the former, he turned to a group of brilliant Greek émigré scholars who had fled to Italy after the fall of Constantinople. Among them was a young man from Crete whose knowledge of Greek literature and language was unmatched: Markos Mousouros.

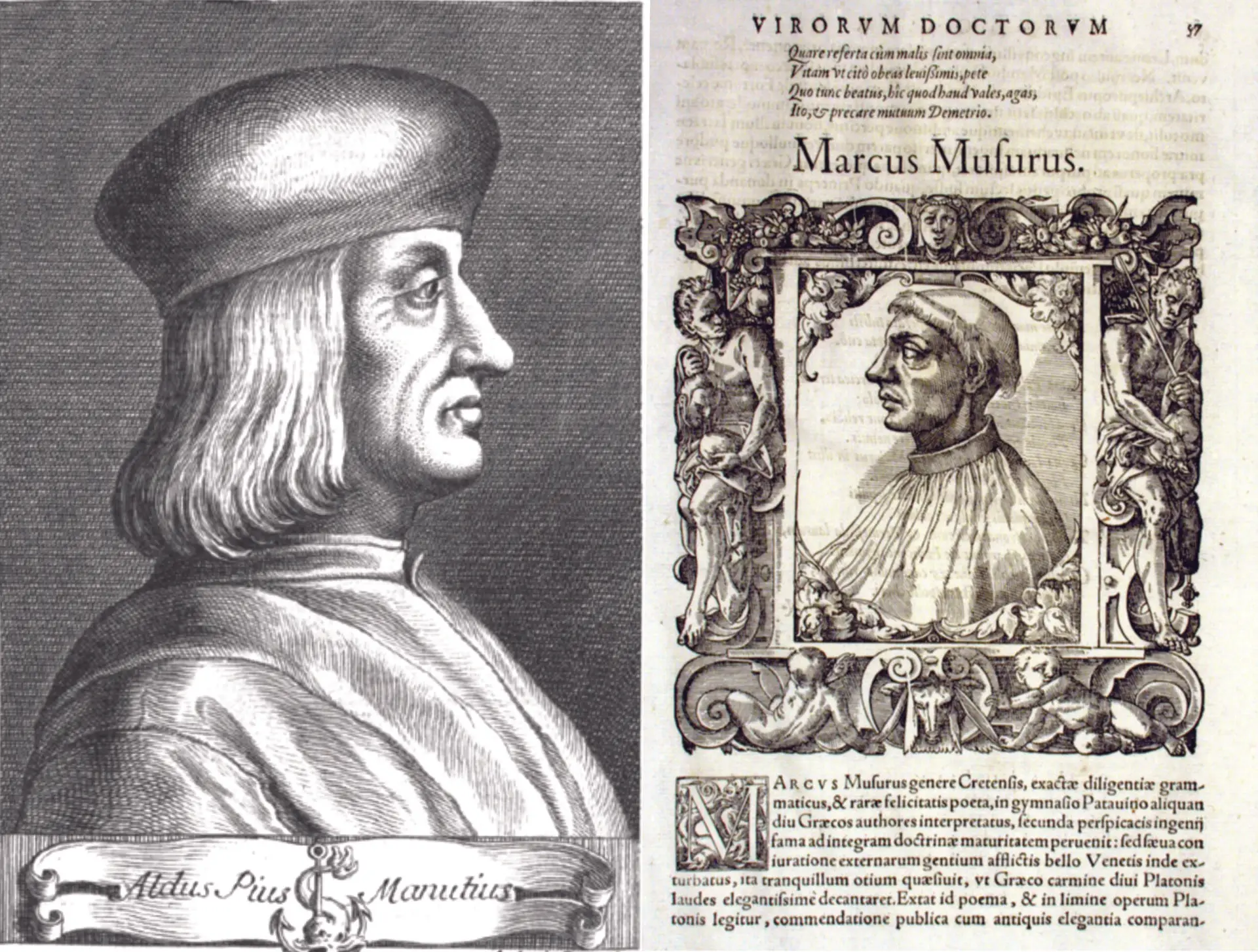

Markos Mousouros: Crete’s Gift to the Renaissance

Markos Mousouros was born around 1470 in Heraklion, then known as Candia, part of Venetian-ruled Crete. From an early age, he displayed a passion for language and scholarship. He studied under the famed Hellenist Aristobulos Apostolis before moving to Italy, where his mastery of both Greek and Latin quickly gained him recognition among humanist circles.

By the late 1480s, Mousouros was living in Florence, studying under the Byzantine scholar Janus Lascaris, and later moved to Venice — the bustling hub of printing and trade. There he began teaching Greek, counting among his students none other than Erasmus of Rotterdam, the great Dutch humanist.

When Aldus Manutius decided to establish a printing press devoted to Greek classics, it was Mousouros who became his indispensable collaborator. He edited texts, corrected proofs, translated where necessary, and ensured that the Greek language — so prone to errors in early printing — was presented with scholarly accuracy and beauty.

In many ways, Aldus was the mechanical genius, and Mousouros was the linguistic soul of the operation.

In 1495, Aldus printed his first dated book — a grammar of the Greek language by Constantine Lascaris. It was the beginning of an extraordinary collaboration between printer and scholar.

Aldus’s dream was not just to publish Greek texts but to reinvent how books were made. The manuscripts of his time were enormous, printed on sheets so large they could barely be lifted. He wanted to “bring the book to the reader,” as he famously put it. To do that, he needed to change the book’s very form.

With the help of a gifted punchcutter named Francesco Griffo, Aldus developed a new, compact typeface modeled on the handwriting of Italian scholars. This elegant slanted script came to be known as “Aldino” — and later, Italic. It allowed him to fit more text on each page without sacrificing legibility.

He also standardized a smaller paper size, the octavo, which could be easily held in one hand and carried in a pocket. These innovations culminated in what Aldus and Mousouros called the “enchiridion” — literally, “that which fits in the hand.”

For the first time in history, books were designed to be personal. They could travel with their owners. Reading became something intimate, private, and mobile.

“Make haste slowly.” Few phrases capture the balance of art and industry as perfectly as this one. For Aldus Manuzio and Markos Mousouros, it meant approaching printing — and learning itself — with both energy and care.

The New Academy and the Cretan Connection

Every printer of the Renaissance had a mark — a symbol that stood as their brand and seal of quality. Aldus chose an image that perfectly encapsulated his philosophy: a dolphin wrapped around an anchor. The image came from an ancient Roman coin and was accompanied by the motto Festina Lente — “Make Haste Slowly.”

The dolphin symbolized speed and intellect; the anchor stood for patience and stability. Together, they embodied Aldus’s vision of printing — work done swiftly but carefully, innovation balanced with craftsmanship.

The logo appeared on every book that left the Aldine Press, becoming one of the most recognizable trademarks in publishing history. To own a book bearing the dolphin and anchor was to possess a masterpiece of scholarship and design.

At the height of his success, Aldus founded what he called the New Academy, a society of over a hundred Greek and Latin scholars who gathered to edit, translate, and preserve ancient texts. Membership in the Academy required that one speak Greek and even adopt a Hellenized version of one’s name — Erasmus became “Erasmos.”

Greek was the working language of this intellectual circle, and Crete was well represented among its members. Venetian rule had turned Crete into a crossroads of Greek and Italian culture, producing a generation of bilingual scholars who bridged East and West.

Mousouros was one of the Academy’s stars. His meticulous editions of Greek texts became the foundation for many of the Aldine Press’s publications, including the first printed edition of Plato’s complete works in 1513, which he dedicated to Pope Leo X. That edition, printed in Greek, remains one of the greatest scholarly achievements of the Renaissance.

It is no exaggeration to say that without Mousouros’s guidance and editorial skill, the Greek classics might not have survived the transition from manuscript to print with such fidelity and grace.

Aldus and Mousouros were not only rescuing texts from oblivion — they were inventing book design itself.

They established many of the principles still used in publishing today: consistent page margins, readable typefaces, proportional spacing, and the relationship between text and white space. They also developed more durable binding methods and set new standards for layout and typography.

Most importantly, they reimagined what a book could be. It was no longer a monument; it was a companion. Aldus’s “handbooks” were bound in soft leather, small enough to slip into a coat pocket. Readers could carry them on journeys, to marketplaces, even to war.

This shift in form changed the psychology of reading. Knowledge became mobile. The Renaissance scholar could now learn on the move — and that simple fact helped spread humanist ideas across Europe faster than any army could march.

The Legacy of Aldus and Mousouros

Aldus Manutius died in 1515, and Markos Mousouros followed two years later in 1517, dying in Rome at the age of about forty-seven. But their legacy was immense.

The Aldine Press continued under Aldus’s family for several generations, and its influence spread far beyond Venice. Printers across Europe copied the Aldine typefaces and the octavo format. The “italic” script, initially a practical innovation, became a typographical standard still used today.

Even Aldus’s dolphin-and-anchor emblem was widely imitated — sometimes honestly, sometimes fraudulently — as other printers tried to borrow the prestige of the Aldine name.

As for Mousouros, his contribution was not only in editing and scholarship but in symbolizing the broader Greek participation in the Renaissance. Cretan and Byzantine scholars had carried the torch of Greek learning to the West, and through the printing press, they ensured that light would never go out.

Fast-forward four centuries to 1939. In the United States, an enterprising publisher named Robert de Graff launched a company called Pocket Books with the backing of industry giants like Doubleday and Simon & Schuster. His idea was to print inexpensive, mass-produced novels small enough to fit in a jacket pocket — and to sell them everywhere from newsstands to railway kiosks.

The first title was James Hilton’s Lost Horizon, which sold 2.5 million copies. The age of the paperback had arrived.

But de Graff’s “pocketbooks” were, in spirit, direct descendants of Aldus’s enchiridia. The same principles applied: portability, affordability, accessibility. The difference was technological scale — mass production instead of hand-pressed pages.

In both cases, the goal was the same: to make knowledge and imagination available to anyone, anywhere.

Next time you slip a paperback into your bag or open a novel on the bus or in the airplane, remember that you are part of a lineage that began half a millennium ago — with a Cretan scholar, a Venetian printer, and a dolphin wrapped around an anchor.

Festina lente. Make haste slowly.